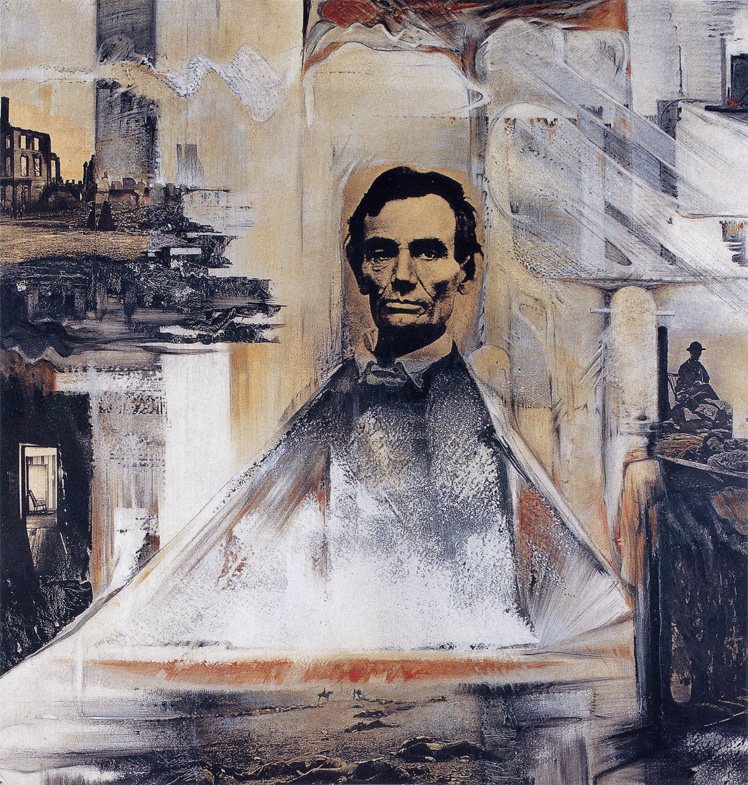

Lincoln #1

48 x 48 inches

Mixed Media with Acrylic Binder on Canvas

This collage includes photographs of battle-ruined buildings in Richmond and a hallway in the house where Lincoln died. The painted, horizontal shapes under the ruined buildings and extending toward Lincoln convey an image of a tattered flag. The cropped photo of a Civil War battlefield, lower center, and the photo of war-ruined Richmond, considered as subjects, can stimulate feelings of the civil War, nationhood, the heroic Lincoln, or other entities by which we map further associations and emotional feelings to the flag.

All my prehensions of these subjects have been public careers even though they are first processed by my private, subjective forms. For example, in Lincoln’s face I recognize the actual entities of assurance, gravity, stability, immanent humor in his lip line and awe in his overall aspect. His head, at larger scale than the other events, suggests importance. The large head, together with his expression of gravity and depth of character, and the pyramidal painted base that supports the head, suggest an overriding force (derived from strain feelings and metaphors of force, rising up and my knowledge of Lincoln’s efficacy). I have a conceptual feeling that might be roughly expressed as follows: Rising up and out of the era indicated by the events of these photos is a certain coordination of facts and myths of American history. Lincoln’s presence looms large. It dominates the scale of the collage and my conception of the era indicated by the photos in the collage. This private realization of Lincoln’s dominance illustrates a passage into a novel stage of publicity.

Whitehead speaks of the subjective passion initiated by public facts, such as the photograph of Lincoln. In this collage, such passion is appropriated from other knowledge of Lincoln and of the world. For example, Lincoln may have suffered from Marfan syndrome, causing the muscles in the right side of his face to sag. This condition is usually considered to be disfigurement. But taken with his other features – the tall, sculptured head, the high forehead, the tousled hair, the chiseled, expressive, potentially bemused mouth and the exceptionally deep-set eyes – the sagging muscles provide contrasts that add notes of profundity, sadness and life to Lincoln’s face. This photograph, with its head-on directness, austere aspect and fascinating contrasts, more than any other public data about Lincoln, grounds my particular subjective passion for his character, his genius and his stature as an historic figure.