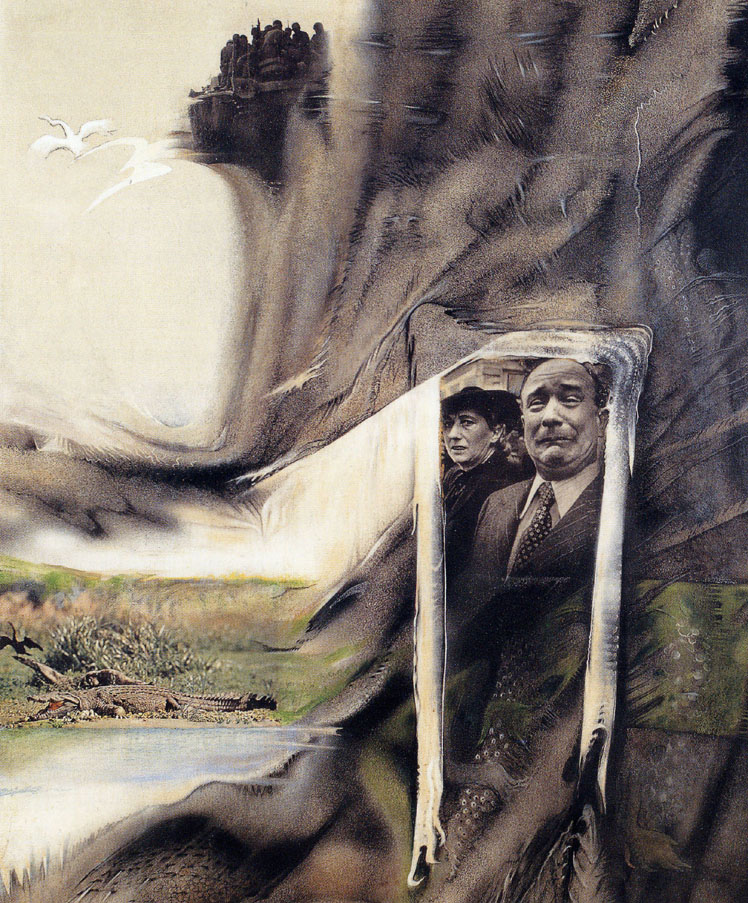

Crying Frenchman

60 x 48 inches

Mixed Media with Acrylic Binder on Hardboard

Eddie Jones Collection

The first time I saw the photograph of a Frenchman fighting back tears included in my collage, I remember thinking with unguarded naiveté, that in the long term, photographs like this would reduce the human inclination to make war because the image elicits such powerful feelings and thoughts of visceral and intellectual strength about personal and national tragedy. This photograph sometimes initiates shock. Some observers give start to a laugh when first confronting the image, as if in uncontrolled mimicry of the man’s lips, and possibly the feeling of relief at being the viewer and not the viewed. Damasio tells us that deep grief and smiles are executed by brain structures located deep in the brain stem. We have no means of exerting direct voluntary control over the neural processes in those regions. Such smiles and grimaces cannot be faked, the illusions of actors notwithstanding. At any rate, I believed that the photograph possessed an organized pattern that produced more intense feelings than that found in most art, making it of exceptional historic and aesthetic interest.

Years later, while watching a television documentary, I saw the same unforgettable image forming before my eyes. The photo had been edited from a filmstrip showing the surrender of French flags at Marseilles after capitulation to the Nazis. Kenneth Clark calls such images movements of visions

It is the sudden awareness of the inexplicable. The flow of accepted associations in which the mind, like a manatee, maintains a healthy torpor – what we gratuitously call the law of nature – is sometimes interrupted and we are shocked to recognize for a second, how odd things really are.

In the photograph, the man is about to weep and the woman is not. The man’s face conveys a sense of grief so profound as to transcend our expectations. The surprising angle of the camera suggests that physical events exist in geometrical relationships beyond our habitual assumptions. These factors sharpen our appetite to find supporting incidents. For example, to feel the background architecture with its stark, black, void and widows as threatening is to support the dread that we feel. I have almost obliterated the windows to concentrate attention on the faces, even though the windows contributed to my sense of the oddness of things, and of a “moment of vision.”

We respond to details in the perceptual world that trigger already harmonized experiences of similar occasions. Although clear and visible details usually initiate our response, it is the rich, invisible background elicited by these cues that gives depth and quality to our experience. For example, it is this background that leads me to conclude that the man and woman are probably French. The particular shapes of the faces direct me to think so, just as past experience leads us to recognize the Slavic “ski slope” of a Khrushchev nose. Of course, I may be wrong about the faces being French, but the point is that I am able to supply a mass of already harmonized experience about French culture and history to flesh out my reality of the image. The man’s straight, stiffened posture and his “French” face suggest Gallic pride, which can become a context for the intense grief that I read into the trembling mouth and eyes. It is French liberty and honor that is being lost, with all the connotations that information brings to the viewer. During a university seminar discussion of this photo, one student insisted the man could be upset over the prospective loss of his business, perhaps making uniforms for the French army, and that his grief might have nothing to do with patriotism. There is no practical way to disprove this assessment, but the fact that the editors of Life gave the image a full page in their large format Picture History of World War Two indicates that, to them, the man’s body language and facial expression communicated not mere personal self interest, but a reverie involving self and nationhood – a transcending idea involving histories of French and other people, living, dead, and imagined. That is the meaning they recognized and believed appropriate to the context of their book and to the interest of potential readers.