Ideation

44 x 72 inches

Mixed Media with Acrylic Binder on Canvas

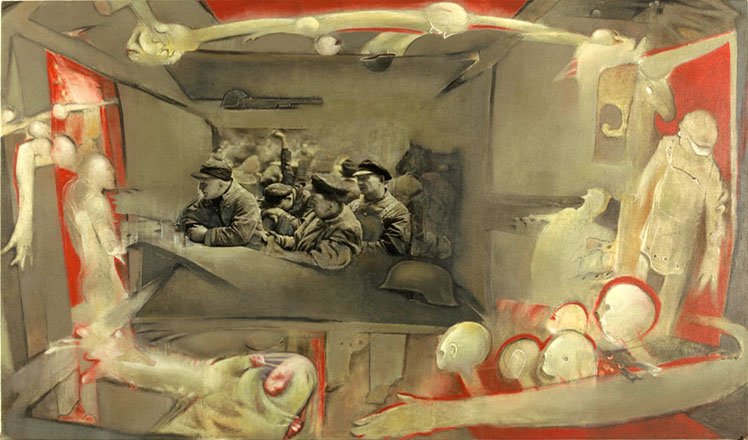

A photograph may call our attention to multiple spatial dimensions, directions and sizes, and other, harder to picture relationships among objects. Occasionally the same photograph may initiate thoughts about immanence that especially inhabit the meanings we derive from the photograph. Cartier-Bresson’s 1950’s photograph (figure 10) of German workers in a large tavern is, for me, a vivid example. The workers form a tableau that expresses tiredness, resignation, class designation, possible ethnicity, and a certain civility. The facial types and the uniformity of grooming and attire suggest a German setting. My latent disposition, formed largely during the war years, to view much about German social and political culture in terms of authoritarian regimentation, fixes on the similarities of clothing, a beer hall gestalt which is not necessarily negative, and other cues to complete a closure of “vaguely negative German uniformity.” If I were to view a photograph of four or five Portuguese fisherman wearing similar clothing while cleaning a catch, I doubt that I would feel “negative uniformity.” This provides an example of how the mind utilizes stored overlays of already harmonized meaning, including time frames, to map cognitive outcomes as directed by the subjective aim or intentionality of the viewer.

The up-stretched arm over the cap of the worker who is face down makes a pointed and somewhat humorous contrast to the tired, down-turning body language of the workers in the foreground. This gesture illustrates Cartier-Bresson’s penchant for catching the whimsical with the serious, suggesting a French rather than German attitude behind the camera. To the rear of the standing workers, out of focus, and fading into the spatial ambiguities of the background, are smaller, seated figures who add scope and contrast to the foreground figures.

I framed the photograph so that the viewer can focus on its contents and its boundary. The gray-green frame was left open at the corners to emphasize the vanishing perspective of the hall and the workers. The frame vaguely suggests a distended Iron Cross. I placed an image of a German helmet at the lower right corner of the “iron Cross” frame to call attention to the way in which hats and clothing shape our response to the photograph and to give a sign of my subjective prehension of a latent militarism. My bias was directed by an oversimplified generalization that the uniformities of the workers – their clothing and expressions – reflect a German uniformity and obedience that contributed to two world wars. The bias led to my readiness to make an Iron Cross out of the frame and to add the helmet. Such associations are obviously subject to error and are subject to revision by adjustments in our thinking. I wish to show that they are inescapable to our mental life in fleshing out the emotional and intellectual content of meaning, an dare part and parcel of the cognitive process.

A Nilsson photograph of a fetus is placed directly under the standing workers. The fetus appears to be clutching the choroids membrane that contains it. The sense of constriction in this fetus image has a counterpart in a sense of the workers as if they are held in thrall. To me, in this context, constriction connotes birth into a socioeconomic setting from which one is unlikely to escape. The inert face of the fetus, with its closed eyes, seems to be without volition and harmonizes with the expression of tiredness and resignation that we find in the face of the worker at out far right. As the far right of the canvas is an enlarged, hand-drawn image of a worker suspended as if he is without volition. The faint image of a horse at the upper left of the worker derives from a “Leonardo stain.” It offers a fuzzy interchangeability between horse and worker via the metaphor of “working like a horse.” In this collage, as in others, I am trying to project an image of an object fading in and out of a background of possible meaning and associations, a symbol of the reality that underlies appearance in which an object requires other objects that are not present for its meaning.

As acculturated viewers we ask ourselves where the workers come from, and what their future holds. We compare ourselves to them, examine their clothing and other cues, and perhaps unconsciously, act out or otherwise engage the up-stretched arm nd their other body postures within our own bodies to arrive at answers to our questions. All this attests to the immanence of interrelationships among all things. That all things are immanent in each other is an idea that rests on philosophic and experiential foundation. For most occasions in our lives we rarely examine the foundation’s condition. Other cultures have developed their own treatment of immanence. Hinduism, with its notions of recycling life, seems more concerned with the idea than we are in the West. But it is the West, with its inheritance of Greek philosophic inquiry into all things, that has led to new conceptions and visualizations of matter and space-time, and whose arts produced Rembrandt, Wright, Picasso, and the sensibility of Cartier-Bresson. As artists, their expressions have captured and advanced our awareness of the role of immanence in our understanding of reality.