Epochal Time

48 x 48 inches

Mixed Media with Acrylic Binder on Canvas

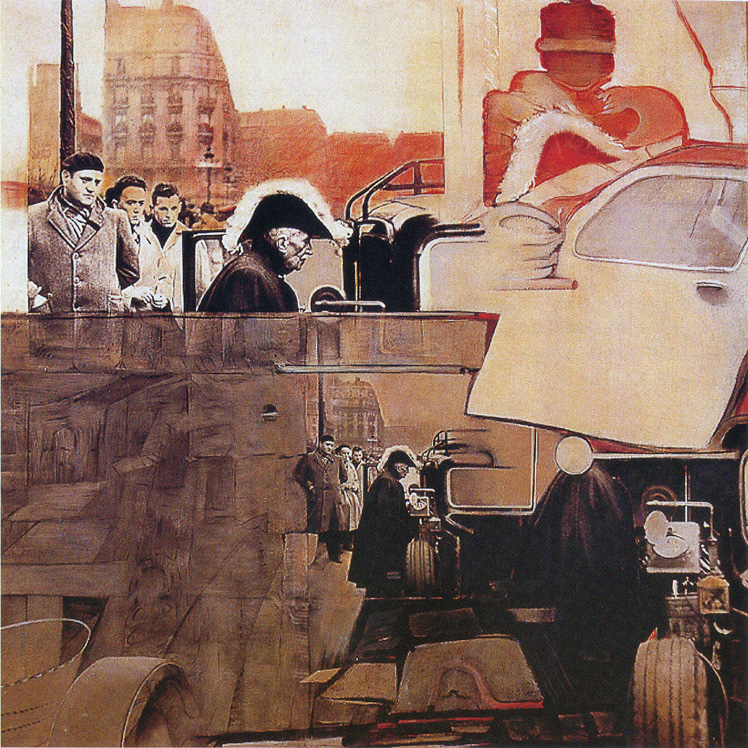

With the preceding commentary as background I want to consider Cartier-Bresson’s photograph, Aged Academic Entering a Cab, included in my collage painting. This extraordinary photograph initiates a sense of the sacred, of value, and of mystery behind the neutral aspect of events to which most acculturated people can respond. The decisive flat plane and larger scale of the aged man’s profile, hat and cloak are seen in forceful contrast to the exaggerated perspective of the cab, on looking men, and background architecture. This geometrical contrast of flatness and depth, felt with my particular body-mind, as has an impact something like the golden mean in the proportions of the Parthenon. It invokes an arresting conceptual prehension of valued order that allows me to feel the other prehensions of content in the perceived event as more positively unified contrasts. In other words, my attention and desire to continue my mental evaluation of Cartier-Bresson’s photograph is stimulated and maintained by this geometrical set as I “map” it with references to concepts such as “suspension in time,” “a distant future,” “a distant past,” and a changing socio-political situation.

The striking hat with honorific plume suggests privilege that possibly descends from the Ancien Regime. The man’s feet are invisible, making his figure seem to float, in rewarding contrast to the hefty bystander in a beret whose feet are firmly planted on the pavement. This contrast enforces a sense of suspension or drifting, a sense that provides a reference frame in which the aged man becomes a symbol of the passage of time and of a social order. The cab, with its perspective overlapping of pipes, rack, braces, mirror, wheel and moldings, appears to me, in context with the aged man, as a symbol of technology about to speed humanity toward an unknown future. The vigorous depth and motion of the tire and the other parts of the cab produce strong tensions against the flat, stable, yet floating plane of the aged man. The contrasts in the images of cab and man produce the shock of collage. In the background, the mansard-topped urban architecture, with its eroded profile, looms like a ruin rising out of a distant mist. The sense of the past conveyed by this French architectural prototype enforces the sense of age symbolized by the man and his rather elegant “French” costume, and the sense of social change in the contrast of the older man with the younger onlookers in their street clothes.

To my eyes, the human transaction in the picture is probably initiated by the hat. In the context of the other data in the scene, the hat’s arresting visual prominence and its rich symbolic possibilities direct the responses of the three on looking bystanders, as well as the viewer of the photograph. The bystanders could be socialists musing over the passage of privilege into oblivion, the idea of mortality, or they could be feeling honorific sentiment. Most likely, in some degree, they may be subject to all these realizations.

The man, in the costume of cloak and hat which suggests authority, is an academic, not a famous political figure as several viewers have supposed. He conveys to me an expectation of respect. The cluster of window balcony railings and shutters look to me, in their shapes, like eight “badges” or “blinders” conveying vague notions of uniformity, and the authority we attribute to the hat prompted my initial painted response, a frontal “head-badge-authority” figure at the upper right, which looked to one viewer like a “tin God.” I felt this was a near perfect response. Prehensions of authority based on class and institutional privilege, the “thinness” of a tin badge, and a blind but ritualized presiding presence through the metaphor of the “tin God” seemed accurate, while allowing the aged man to retain prehensions of respect and the span of human life.

The major stimulus for these notions of authority is the hat image, which I acknowledge and repeat below the “head-badge.” Nascent fingers descend from the “head-badge,” as if to make contact with the photographed hat and its significance. Below the painted hat is another set of larger fingers that touch the car door and hold a match to acknowledge incidents in the photo. The cigarette-match incident – possibly a sign of urban sophistication and, more recently, a health hazard – many seem outside the main closures of meaning, and yet add content to the context of the wider world.

The sacredness we find in the photograph lies in the way it allows us to map already deeply harmonized human interests into an incandescent concentration. As we view the photography, we orchestrate notions such as civilization, French nationhood (in my case prompted by French elegance in the shape of the hat, the Parisian mansard roof which was originally conceived as a tax dodge, now seen as a “humanizing” visual stimulus, the beret, and the faces of the bystanders), mortality, destiny, and the passage of time into poignant human terms. This orchestration arises out of the contrasts in the photograph set up by its powerful design pattern. We may take pause at the passion that we feel in the face of information which appears so dispassionately before us. While the data in the photo may be theoretically neutral as mere phenomena, it is never neutrally entertained. Our response depends on our individual values, aspirations, and participation in an imagined history. It is Cartier-Bresson’s genius as an artist and observer and his “knowledge of the world,” as I once heard him tell a television interviewer, that enabled him to see the possibilities developing as he moved in to capture the moment.