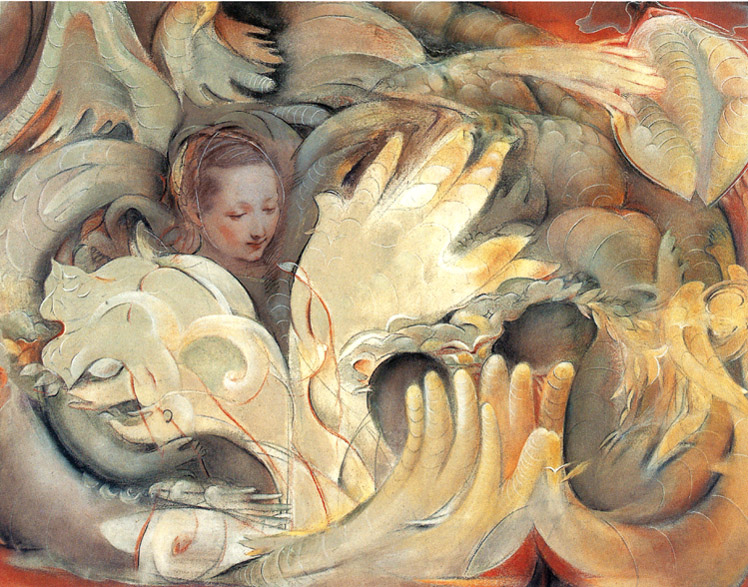

Spirit in the Body

36 x 48 inches

Mixed Media with Acrylic Binder on Canvas

Thad Kusmierski and Anna Berger Collection

Barocci’s Head of the Virgin combines the beatific sweetness, selfless detachment and otherworld ideality projected by Medieval artists in the sculptured portals of Chartres with the image of a corporeal, natural, human persona attained in the Italian Renaissance. With disarming assurance, the drawing synthesizes cues of tenderness, grace and accessibility that Western culture has come to associate with the Virgin, abetted by images, such as the Barocci, in which there are no cues to distract from the drawing’s message of sweetness and detachment. Compare Barocci’s drawing with Leonardo’s Head of a Woman from the Louvre. The hair and ear of Leonardo’s woman are formed into spirals that evoke his studies of water and energy. The chiaroscuro of the eye, lips and neck admit such ambiguity. These cues, suggesting brooding, intensity and mystery, are signs of Leonardo’s genius and complexity, but would distract from Barocci’s simplicity and directness. With the Barocci, we feel surprise, delight and freshness at his capture of grace within the countenance of a palpable person.

How does the artist achieve this response? He enforces a sense of the reality of his subject by the masterful anatomy of the head and the spontaneity and realism with which he renders the sash and hair. Spontaneity and realism suggest the here and now, which provides a contrast to the sense of detachment and to the spiritual. The broad forehead and the wide spacing between the eyes contribute to a feeling of calm. The narrowing chin and, particularly, the small mouth, slightly pursed, with lovable curves, contrast to the slightly plump face and contribute to the “sweetness” of the Holy Mother. The becalmed expression and immanent smile let us impute an objectification of the sacrament, defined by the Anglican Book of Common Prayer as the outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace. The firm, ovoid outline of the head conveys a notion of geometric containment derived from classical Greece, while the face itself invites our gaze because of its projection of an unselfconscious state of being.

I have responded to the Barocci in my first drawn gesture by framing the head with wing like, oversized “hands” and “drapery” to help locate the head within the picture and to communicate both surprise and affirmation. These wing-hand forms encompass the head and touch the suggested body of the Virgin, as well as the surrounding background forms, as to suggest that these forms are together in a continuum. Suggestings of fingers and feathers emerge from a background of curving, convoluted, whitish, gray-green shapes. The cues of feathers relate to the hand-wings-drapery that address the Virgin’s head and the angel at the far right. The gray-green shades around the Virgin’s face are extended to the surrounding areas. The intention is to suggest an image of particular thoughts coming into the mind – a necessary context for any object of perception.

I extend the imaged “continuum” into forms of fingers that are uplifted in a sign of prayer. This sign of prayer is not bounded by a concept of the virgin mother, but may also be understood as a sign of the idealized transfer of Mary’s virtues to an homage to actual women, which the British historian W.E.H Lecky identified with the rise and influence of rationalism during the Renaissance. Located on the bottom right, these praying fingers are extensions of billowy, curving, cylindrical forms that frame a dark cleft under them. The cleft suggests and anatomical orifice, a cut, a wound, or the vertex of the painting’s merging and emerging curving forms. There is allusion to female sexuality in the painted background. This refers to the sensual and sexual in human existence, somewhat in the sense of tenth-century Hindu sculpture, in which the sexual integrates in full and seamless forms expressing cosmic wholeness. The suggestion of the spiritual connected to the libidinal, as in western notions of Eros, is also intentional. Lakoff and Johnson tell us that it is the body that makes spiritual experience passionate. The body brings intense desire, and pleasure, pain, delight and remorse. Without all these things in the background as contrasts, spirituality is bland.

I also wanted to suggest the infusion of an object with a sense of a particular memory of form. In this case I abstract or separate out an elliptical form, upper right, based on the outline of the head with its Greek overtones of containment, and show it being touched as if approached by extensions of the continuum representing fingers or feathers. The interior of this ellipsoid is rendered in such a way as to suggest that it is of stuff similar to the continuum. This detail signifies notions of a thought-entity separate from, but without complete detachment from the continuum. The ellipsoid is also symbolic of my subjective aim – the desire to understand, with the fingers that touch the ellipsoid as a sign of that desire – and of abstracting ideas during the rationalization process.

To fortify notions of religious iconography pertaining to the Bible and Greco-Judaic tradition, I have placed a smaller-scaled figure, robed, winged and haloed, emerging from the lower right of the picture – an angel bringing good news. To tie the Virgin’s heavenly yet earthly face into the picture, simplified outlines of anatomical parts extend from the head to the body of the woman. Breasts and an erotic swing of the hip are evident, but not too prominent, in the outline of the body, as is a pregnant belly in the background forms of the continuum. The curving, rounded forms surrounding the head suggest drapery, adumbrated angels’ wings (in the upper left corner), the organic, the physiological and brain tissue. I am far from satisfied with the circling progressions of white lines as symbols. They are supposed to indicate energy, motions, spatial extension, representations of growth, pulses of life, and continua of serial time. The simplified surfaces and outlines are supposed to suggest the denotative and conceptual rather than literal nature of the wings and tissues that are referred to. But my progressions of white lines seem too weak for a graphic representation of such complexity. If anyone has a better idea I would appreciate them sending it to me.

The crudeness of the winglike hands and the ambiguous, unfinished outlines of the implied figure of the woman suggest that one’s ideas are never complete, and that my treatment is a sign of thoughts in a state of transition.

Barocci’s head elicits a strong feeling of the time and place in which it was created. The ideas that it communicates are so surely felt and expressed, and have so long since shifted, that no artist living today could create the equivalent. I want to place the head in an environment that encourages the viewer to rediscover the artist’s achievement and to recognize the continuum of thought by which one takes up details to make meaningful closures of the head in a process of perception and contemplation.