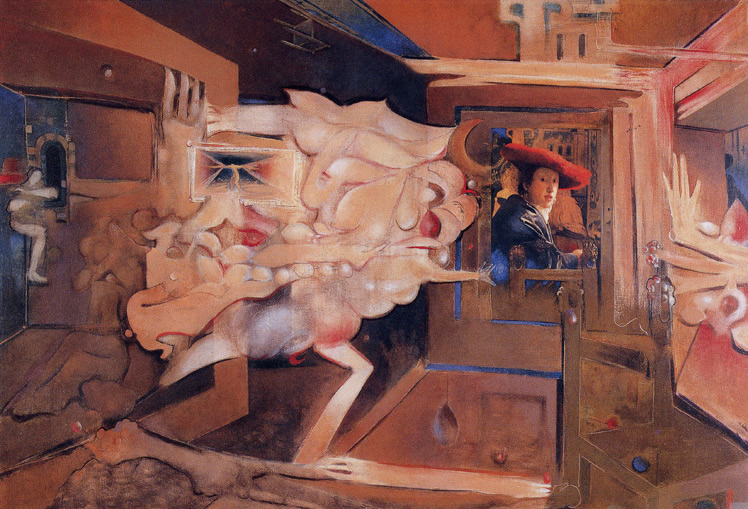

Girl in a Red Hat

42 x 60 inches

Mixed Media with Acrylic Binder on Canvas

For Whitehead, the word “object” means any entity that can be felt and  objectified. My Collage with Vermeer’s Girl in a Red Hatand the Mayan Maize God show figures that project sentience. In both, sentience is expressed as a potential capacity for thought not yet called into action. Data such as open lips initiate the feeling of sentience. Such a feeling can be treated as an object. As such, it becomes a transcendent element characterizing that definiteness to which our experience has to conform.

objectified. My Collage with Vermeer’s Girl in a Red Hatand the Mayan Maize God show figures that project sentience. In both, sentience is expressed as a potential capacity for thought not yet called into action. Data such as open lips initiate the feeling of sentience. Such a feeling can be treated as an object. As such, it becomes a transcendent element characterizing that definiteness to which our experience has to conform.

Further, when we recognize sentience as an object, abstraction enters into perception. Thus to recognize an object an object is to abstract from its prehensions. In the head of the Mayan Maize God, parted lips could just as well be associated with the adenoids and a dull intellect. But in context with the downcast eyes that are without pupils, we are likely to feel submission and the impersonal, and with the strong feeling of awe that is projected by the face we can dismiss adenoids as a negative prehension and let our feelings be dominated by sentience, awe and submission. The strength of this particular image resides in our ability to retain the focus of each of the several feelings- awe, sentience and submission- in the concrescence and continuing through satisfaction.

The Mayan head with its long Mayan nose and upturned Asian-Mayan eyes is framed by a headdress, indicating aristocratic, royal or defied status. These cues contribute to notions that the face represents societal belief rather than a personage or portrait. Thus the objects “awe” and “submission” in the face of the Maize God become transcending elements, definite forms to which our experience (Mayan, late twentieth-century social American, adenoidal, and so forth) has to conform or be rejected.

In this collage, the parted lips and the object sentience are involved in a more subtle event structure with more terms to consider. The young women’s eyes are directed toward the viewer. Their expectancy and possible aggresivity compel our attention. At the same time the young woman is not committed to action. Her parted lips are members of a pattern of highlights and shapes that evoke notions of limpidness, spaciousness, pearl-like translucence, and the necessity and luminosity of light. The lips, though beautiful, are expressively ambiguous. In context with the face and bodily gesture, they convey a hint of displeasure, which contributes to the “stand-back” expression of the face. Physical feelings of arrest, thrust and parry are evoked by the direction and shape of the hat, by the three windows in the tapestry behind her hat with their arresting pattern and look of wide open eyes, and by the forms of the lion’s-head chair terminals, which I see as resembling clenched fists. These feelings harmonize with the woman’s expression of ambiguous reserve and surprise, and provide forms or definiteness even more complex, if less powerful, than in the Maize God example of awe and sentience. Vermeer involves us in complex ambiguities. Is the woman about to greet or to rebuff? Suffused with feelings of immanence, where is she going and from whence has she come?

I have discussed Whitehead’s treatment of how misconception of the universal entered into modern thought through the “sensationalist” philosophy of the seventeenth century. I have attempted to show the influence of this doctrine on the attitudes of some twentieth-century artists, and believe that this misconception is the root of much “nonobjective art”- art that can quickly lose interest for so many viewers and that propagates an excessive subjectivity, which encourages viewers to find the “path of enlightenment” in a single, straight, black line running across a white canvas. Of course, we all attach emotional significance and narratives to symbolic forms that fashion, social consent, superstition and intellectual status supply with appropriate appetitions and justifications, such as the status conferred by some on upper class vocalizations of vowels and consonants in Massachusetts, Nike World’s use of Nazi designs, the dolls in voodoo medicine, or the image of the Holy Mother in some perceptually-ambiguous object or reflection. Nonetheless, both loss of interest in some minimalist art and unchecked subjectivity cannot be attributed merely to Philistines in our midst. I close this essay with a few comments on Whitehead’s explanation of causes rooted in the “sensationalist” tradition.

Strength of aesthetic experience is based on long-repeated and deeply established meanings of subjects and objects, such as light, darkness, budding plants, human and animal nature, motherhood, freedom from slavery, nuanced eroticism in lips by Vermeer, or the satellite photograph of incredible activity of the sun’s surface, that are brought forth in concert with fresh feelings and concepts and reconstituted in an act of concrescence. Sense presentation requires vivid details triggering such already richly mapped entities to establish an individuality with its significance embodied background, which Whitehead calls an “it.” Whitehead stresses that the sense of an individual “it” can be distinguished from its qualitative aspects. Even a dog smells in order to find out if a person is that “it” to which its affections cling, and Roland Barthes, in his book Camera Lucida, can claim that his favorite photograph of his mother barely brings him to touch with the outlines of his fondness for her. The emotional significance of an object divorced from its qualitative aspects is at the base of family affection and the love of particular possessions. Such examples illustrate how the power of an already harmonized background of experience can inform a sense object. Perceptual situations, such as a square of color on a canvas as the presentation of an essence in itself, while allowing the viewer to meditate on the color, merge with it or be repelled by it, according to Whitehead, cannot conflate a real history. It can only present “sensation and a top dressing conjecture, agreed upon by social consent if you are a high brow intellectual when you follow the current reactions of Greenwich Village and Harvard, if you are American, and of Bloomsbury and Oxford, if you are English.”

Thus, the basis of a strong, penetrating experience of Harmony is an Appearance with a foreground of enduring individuals carrying with them a force of subjective tone, and with a background providing the requisite connection. Undoubtedly, the Harmony is finally a Harmony of qualitative feelings. But the introduction of the enduring individuals evokes from the Reality a force of already harmonized feelings which no surface show of sense can produce. It is not a question of intellectual interpretation. There is a real conflation of fundamental feeling.